On the topic of: Pirates, Patriots, & Printers

'Teach' would be the second and final verse a young Ben Franklin would publish in 1719.

The 13-year-old had a knack for writing, along with a passion for consuming all books on politics, religion, philosophy, and early iterations of newspapers from London.

It's a skill he was introduced to four years earlier by his uncle (also named Ben), a self-proclaimed poet who moved in with the family in 1715.

While Ben was being introduced to writing, his older brother, James, was in London finishing his apprenticeship at a printing house.

Then, in 1717, James did what any kid does in their early twenties… he moved home and asked dad for some start-up money for a totally cool project that he didn't really have a plan for yet.

James had seen the progressive pamphlets and newspapers in London and wanted to recreate something of his own in Boston. Remixing English entertainment for an American audience made him very ahead of his time.

But before James could start his own printing house, he needed a loan.

“While Josiah had James in one ear, he had his youngest son in the other.”

Ben was a bright kid who did not want to follow in his father's steps to become anything ordinary or pious; he wanted to be out at sea, traveling, exploring, not being home. He was the prototypical too-smart-for-your-own-good youngest child who was going to find a way to do what he wanted, and his father probably sensed that.

Ben's father, Josiah, had already lost one son at sea and did not plan on losing another, especially during the Golden Age of Piracy (which was a real thing).

“Side note: Ben and James were two of ten children from the same parents (including one brother named Ebenezer, gross), and had seven siblings from their father’s previous marriage ... Josiah busted. And yes, this means Ben Franklin was the youngest of 17 kids. ”

Josiah agreed to give his son the loan he needed for a printing house if he took on Ben as his apprentice. As much as Ben would have rather been at sea, at least he was going to be surrounded by books, something he was already comfortable with.

I wonder if James knew his brother was talented when he had Ben write a verse about a recent lighthouse fire? Being the youngest myself, being given a task was usually a way to keep me busy and out of other people’s business.

Either way, Ben admits the verse "sold wonderfully" in his autobiography. The sales and popularity of the pamphlet proved that he had potential as an author and proved that adults couldn't tell that he was only twelve-years-old.

A second verse quickly followed.

In March 1719, Edward Teach (a.k.a. Blackbeard) was captured and killed off the coast of North Carolina. Young Ben recounted the drama of the infamous pirate and the final battle in his second verse, ‘Teach,’ which was published and sold decently well. Ben wrote about the drunken pirate that spewed curses and cannon fire for, apparently, hours before boarding a captured ship where a crew lay waiting to ambush him. Shot and decapitated, Blackbeard’s head was mounted to the bowsprit of the naval ship as it sailed back to Virginia.

“Side note: ‘bowsprit’ is exactly what you think it is... the long stick on the front of an old ship. Where else would you put a pirate’s head? Also, am I the only one who didn’t realize pirates were a thing in early America?”

Pirate battles sound like a pretty sick story for a young kid to cover. Especially for one who would rather be out at sea himself.

Question: Would you hate me if I compared Ben Franklin to Billie Eilish? Hear me out, the obsession of a thirteen-year-old plus the natural talent for their craft and the help of their older brother... Am I saying Billie changed music like Ben changed America? No?

This is dumb, let’s get back to business.

The main problem the Franklin brothers faced with their publications was the opposition from religious leaders in town. It had been the job of ministers to contextualize life and death and the brothers decided to take a sensationalized approach to the topic. How American.

Josiah Franklin, their father, was also the silent partner for the printing house and a hopeful church deacon. After ‘Teach’ was published, Josiah quickly extinguished any thoughts of Ben publishing more of his writing, no doubt adding to his later beliefs on free speech and freedom of thought.

“WITHOUT Freedom of Thought, there can be no such Thing as Wisdom; and no such Thing as publick Liberty, without Freedom of Speech; which is the Right of every Man, as far as by it, he does not hurt or controul the Right of another: And this is the only Check it ought to suffer, and the only Bounds it ought to know.”

A few years after ‘Teach’, Franklin’s printing house started producing a wildly popular newspaper, The New England Courant, which had no rival in its criticism of religion, society, government, and social norms. And Ben was still unable to publish content.

The New England Courant’s inaugural issue asked readers to send in essays, poems, and everything in-between as long as it was amusing. The small staff that worked in the printing house took the liberty of using this to start or continue public conversations under pseudonyms.

This early version of The Daily Show took its idea from a London publication and re-envisioned it for a young America, with James Franklin as its Jon Stewart.

“Side note: Yes, it even has it’s own version of Craig Kilborn, it’s these two guys named Douglas and Checkley. Is this analogy a stretch? Yes, but that’s beside the point.

Focus, people.”

James drove his conversations dangerously close to the Sun more than once, getting under the skin of the rich, elite, and anyone in power. His newspaper begged the government to arrest him as it reflected on the their behavior and opinions. So much so that on June 12th, he was summoned to appear before the Royal Governor and his Council for issues with his paper’s most recent publication.

James refused to expose the author of an article criticizing Boston’s lackadaisical response to an attack, and continued terrorist threat (their words, not mine), from the dreaded pirate, Ned Low.

James was imprisoned.

The craziest part of this story is that this dude, Ned, was a Boston pirate. Which made me think that pirates are just mobs on boats, and some of them are just assholes from Boston. But that’s another conversation.

Ned Low is said to be one of the most vicious and barbaric pirates of the Golden Age of Piracy. His specific talents came in the form of tying someone’s hands together with rope between their fingers and setting it alight until all that was left were bones… just as an example.

Ned grew up in poverty in London, running wild in the streets as a child, pickpocketing, stealing, and gambling. He moved to Boston when he was 20, traveling to the New World alone in 1710.

He fell in love but his first son died as an infant and then his wife died giving birth to their daughter. To recap, he’s an illiterate d-bag with unresolved issues and he abandoned his daughter.

It’s the role Casey Affleck was born to play if I thought he was a good actor.

And every Mark Walberg movie has taught me, ‘once a criminal, always a criminal,’ so it’s no surprise that this loaded gun of a young man quickly became a match for only Ramsey Bolton. We all remember Ramsey Bolton, right? Remember, when Game of Thrones was good?

This guy Ned brutally tortured his captives and in 1722, he targeted trade routes between Boston and New York.

James’ newspaper, The New England Courant, published the news of the pirate’s attacks with the clear implication that Boston, compared to Rhode Island, was taking their time to deal with the threats.

“...the Drums were order’d immediately to be beat about Town for Voluntiers to go in quest of the Pirates; and by 3 of Clock the same Day, there were two large Sloops under Sail

We are advis’d from Boston, that the Government of the Masschusetts are fitting out a Ship to go after the Pirates, to becommanded by Capt. Peter Papillion, and ‘tis thought he will sail sometimes this Month, if Wind and Weather permit.”

James was imprisoned with no trial for refusing to reveal the author of the article and soon after, Young Ben was asked to appear before the same council. Ben, however, was able to walk out of the meeting without imprisonment and without divulging any secrets.

At 16, Ben was still an indentured servant to his brother and that’s all he told the council. He said that it was the duty of an apprentice not to tell the secrets of his master… something I’m sure everyone on the council hoped their apprentices would also say on the matter.

Young Ben was the Stephen Colbert to James’ Jon (if we discount the brothers cold and sometimes abusive relationship). Ben had spent every day for the better part of four years reading everything he could get his hands on and even bought books he couldn’t borrow using the money he saved from becoming a vegetarian and therefore needing less lunch money per day (something he read in a book about living a longer, healthier life).

He listened to all the young minds of the time talk, debate, push the boundaries of their authority as citizens, and as the press. And he studied James’ newspaper, it’s content, and the way James crafted an issue.

So when James was imprisoned, 16-year-old Ben stepped up to produce and publish the newspaper’s following issue on time and as sharp and entertaining as it had been.

It started with a letter from a regular contributor on the matter of freedom of speech:

“It may justly be said in its Praise, without Flattery to the Author, that it is the most Extaordinary Piece that ever was wrote in New-England. The Language is so soft and Easy, the Expression so moving and pathetick, but above all, the Verse and Numbers so Charming and Natural, that it is almost beyond Camparison.

The Muse disdains

These Links and Chains,

Measures and Rules of vaulgar Strains,

And o’er the Laws of Harmony a Sovereign Queen she reigns”

Silence was a young widow who had captured the hearts of Boston after responding to James’ initial request for interesting content.

The whole letter (one of fourteen that would be published in total) was a delicious criticism of the New England writing style outside of the Courant. To prove how mundane other writing had been, she offered up a recipe to create your very own funeral column in the only way it would be approvable by the government.

To start, take a neighbor who has recently died, preferably one of a sudden and tragic death.

“To these add his last Words, dying Expressions, & C if they are to be had, mix all those together, and before you strain them well. Then season all with a Handful or two of Melancolly Expressions, such as; Dreadful, Deadly, cruel, cold Death, unhappy Fate, weeping Eyes, & C.”

Ugh, it’s so good, right?

“Have mixed all these Ingredients well, put them into the empty Scull of some young Harvard; (but in Case you have ne’er a One at Hand, you may use your own) there let them Ferment for the Space of a Fortnight, and by that Time they will be incorporated into a body, which take out, and baying prepared a sufficient Quantity of double Rhimes, such as, Power, Flower; Quiver, Shiver, Grieve us, Leave us; tell you, excel you; Expeditions, Physicians; Fatigue him, Intrigue him, & C. you must spread all upon Paper, and if you can procure a Scrap of Latin to put at the End, it will garnish it mightily; then having affixed your name at the Bottom. with a Moestus Composult, you will have an Excellent Elegy.”

Silence Dogood, the pseudonym, couldn’t be more fitting for Young Ben. And as we said before, Ben was the too-smart-for-their-own-good, youngest child, who’d probably find a way to do what they wanted to do.

Silence was Ben’s way of giving himself a voice; young, educated. thoughtful, and enlightened. Silence spoke about matters specifically and tangentially related to the ideals of being a free man, ironically, as a woman with wit, sarcasm, and spunk.

Ben disliked his brother but proved to be James’ most loyal supporter of the Courant and of James himself. He boldly stood up to the council for James and quietly became one of the most popular contributors to his paper, Silence.

The following letter from Silence (issue number 49 of the Courant) included a piece from a “Cato Letter.”

“WITHOUT Freedom of Thought, there can be no such Thing as Wisdom; and no such Thing as publick Liberty, without Freedom of Speech; which is the Right of every Man, as far as by it, he does not hurt or controul the Right of another: And this is the only Check it ought to suffer, and the only Bounds it ought to know.”

Both Franklin brothers had studied the essays known as “Cato Letters,” a collection of articles published in the London Journal at the time that focused on the principles of a republic and the warnings of a tyrannical government.

James saw an opportunity.

The Courant could publish Cato’s warnings of tyranny and the freedoms of man without being a direct criticism of the Massachusetts government if they reported that the articles existed. Any conversation about the ideas would just be comments or quotes on someone else’s work about someone else’s government.

Cato had been the enemy of Julius Caesar, a champion of republican ideals, and been the namesake of these London essays.

Silence included the following quote in her reprimanding letter,

“...and in those wretched Countries where a Man cannot call his Tongue his own, he can scarce call any Thing else his own.”

It’s fascinating that the idea of America was formed when Blackbeard still roamed the seas and newspapers were still new.

To paraphrase Jim Halpert imitating Dwight Shrute:

[Jim] Question: what type of printers are best?

Printers who publish pirates.

Printers, pirates, patriots of America.

…

America!

[Dwight] … America!

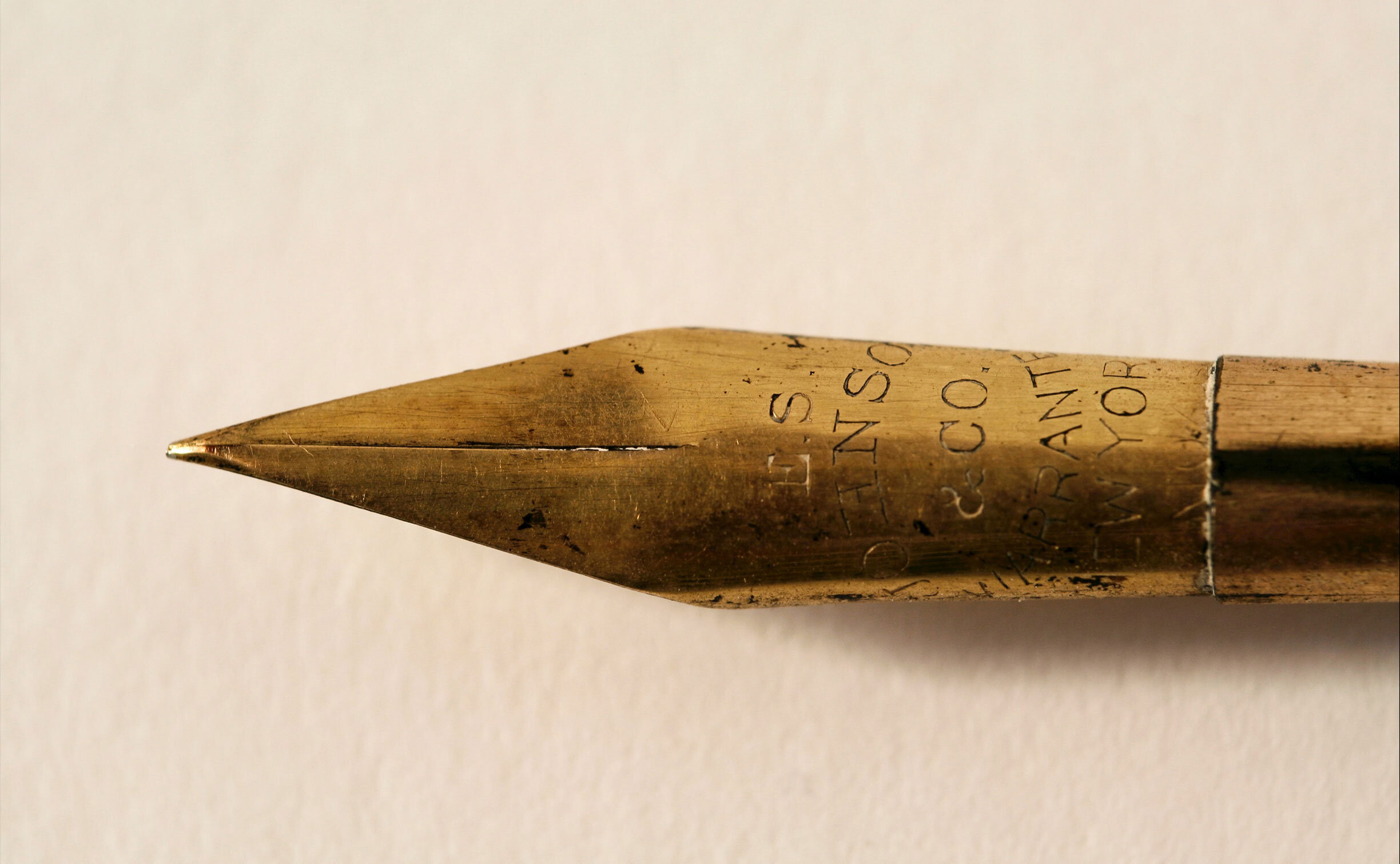

Want to see what the pages looked like?